Morehouse School is the one all-male traditionally Black faculty within the nation. A not too long ago printed guide argues that, consequently, the establishment is uniquely affected by, and in addition perpetuates, particular concepts about what it means to be a Black man in America, together with the concept Black males are “in disaster” and Black male college students have a duty to uplift Black communities by their tutorial and profession success.

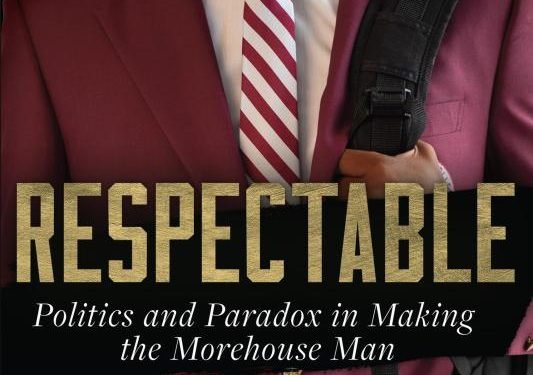

The guide, Respectable: Politics and Paradox in Making the Morehouse Man (UC Press), bases its conclusions on a sequence of qualitative interviews with alumni. The writer, Saida Grundy, is a graduate of Spelman School, the traditionally Black ladies’s establishment situated throughout the road from Morehouse, and an assistant professor of sociology, African American research and ladies’s and gender research at Boston College. She responded to questions on her guide through e mail.

Q: Based mostly in your interviews with graduates, what characterizes the Morehouse model? What does it imply to graduates to satisfy the beliefs of being a “Morehouse man”?

A: Within the guide I describe a number of cases the place all of the respondents interviewed described both the Morehouse model or the Morehouse man (and sometimes each). “The Morehouse Man” is the embodiment of the model. Contributors burdened how the Morehouse man was profitable—which just about at all times meant profession success measured in cash or profile or each. The Morehouse man embodied a sure form of Blackness—he wasn’t a sellout, however he was concurrently palatable to whites, particularly in skilled endeavors. They obtained very detailed in describing how the Morehouse man dressed impeccably in fits, ties or skilled apparel, how he was well-spoken, at all times on time, tidy and a frontrunner.

In reality that high quality of management was the most typical attribute ascribed to the person and the model. These males noticed a Morehouse model that produces leaders and noticed Morehouse males as leaders. Simply who they have been main was somewhat murkier to reply for a lot of males, as was the query of what qualifies one—except for being a product of Morehouse—to be “a frontrunner”—through which they virtually at all times implied management in Black communities and areas. However this almost synonymous very best about Morehouse males being leaders on the helm of the race was actually embedded into all of the methods males talked in regards to the establishment and the way they rationalized an array of practices that outsiders could not perceive as being obligatory or productive for a school expertise. I believe it’s important for the reader to know that what could appear uncommon and even superfluous from the skin is actually steeped of their shared ideology that Morehouse is producing males who will higher the race. That’s what the Morehouse man means for them. The query for me is what’s behind what they take into account a “higher” race.

Q: How have been messages about Black masculinity communicated to college students at Morehouse, based mostly in your analysis?

A: First, I’ll say these messages have been communicated unceasingly inside the establishment such that behaviors, areas and in any other case meaningless options of institutional life have been considered having meanings about gender and Black manhood. For instance, this was the ’90s and 2000s, when most of my respondents have been at school—pre–digitized registration and monetary support. Standing on line for hours for a registrar or support officer could appear extra like a nuisance than anything to school college students elsewhere, however for Morehouse college students getting by and coping with institutional inefficiencies or faulty processes have been reinterpreted as “grit” or some measure of how solely those that can endure or circumnavigate obstacles get to turn out to be “Morehouse males.” Thoughts you, we’re speaking about workers and bureaucratic inefficiencies that basically don’t have anything to do with college students, and but college students made which means in regards to the form of man they’re based mostly on their potential to get by them.

So Black masculinity actually has a number of methods of being communicated. There may be the “direct to client” model through which college students are actually informed by workers, directors and different college students that rituals, curriculum, guidelines and restrictions are about making them a sure form of Black man, and even that they’re obliged to those guidelines, and many others., due to Black manhood and their responsibility to turn out to be leaders. However then there may be simply as actively the reflexive messaging, the place males apply meanings about Black manhood to experiences after the very fact—experiences, as I’ve talked about above, [that] usually have little if something ostensibly to do with race and gender. So Black masculinity turns into the lens by which males see their expertise. What they perceive, what they justify, what they’re informed, what they’re instructed, is constantly filtered by this rationale that this makes them males or higher Black males.

Q: How do you assume the norms set for Black males at establishments like Morehouse have an effect on Black ladies and Black college students of different gender identities and expressions?

A: I actually recognize this query, as a result of a driving argument on this guide has been that narrowly setting up and institutionally grooming Black masculinity the way in which Morehouse does isn’t nearly Morehouse in any respect. It’s a few bigger context of Black gender politics and who will get to dictate what’s necessary for the race’s progress by controlling gender and sexuality politics inside the race. Morehouse is simply an institutional embodiment of a a lot bigger political ideology that Black male elites (college-educated clergy, enterprise leaders, politicians, and many others.) should not solely the rightful leaders of the race however that what’s finest for the race is what’s finest for these males. Black gender politics, like all gender politics, are relational. Yoking what’s finest for the race to what’s finest for its straight, cisgender, “respectable” college-educated males comes at a extreme value to the visibility and precedence of points that have an effect on Black everyone else.

Within the guide, I clarify that my work picks up an ongoing tutorial dialog about how political priorities inside Black communities and areas are fashioned. In describing why Black voting patterns are so comparable throughout revenue and gender demographics, political scientist Michael Dawson clarify that African Individuals maintain to a “linked destiny” ideology that what occurs to the least amongst our race impacts us all. His colleague Cathy Cohen challenged this pondering by declaring that if it have been true, then the HIV/AIDS disaster ought to have been high precedence inside Black politics, as a result of it [by] far and disproportionately affected and killed Black sufferers. Who it was affecting, nevertheless, have been largely low-income and disproportionately queer Black individuals whose points and visibility [are] hypermarginalized inside Black neighborhood politics. I’ve bookended Cohen’s declare by declaring that we should take a look at probably the most privileged African Individuals—“respectable” Black male elites—to know who controls what social points get prioritized inside Black areas. I present that the price of upholding the respectable picture of Black male elites comes at a price to Black everybody else. Points that have an effect on this group of males get solid as urgencies for the race as a complete, and varieties of gender and sophistication hierarchies and oppressions that happen inside the race usually serve the curiosity of that group of males sustaining their energy and visibility as racial leaders and representatives.

Q: You write that Morehouse School’s mission, and initiatives like Obama’s My Brother’s Keeper, advanced partly in response to the “rhetoric of Black male disaster,” the concept Black males have been failing to thrive, and the futures of Black communities hinged on their “respectability” and academic {and professional} success. Through the pandemic, there’s been plenty of concern amongst campus leaders about enrollment losses amongst Black males, and a few schools have not too long ago launched new initiatives devoted to their enrollment and retention. What do you consider these discussions and efforts taking place in academia proper now within the context of your analysis?

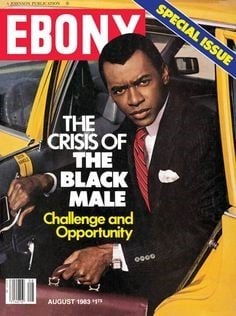

A: Nicely, this concern in increased ed about “the Black male drawback” in enrollment and retention shouldn’t be new. In reality, it has its origins within the Nineteen Eighties, and we must always pay explicit consideration to a 1983 “The Disaster of the Black Male” particular subject of Ebony journal that I cite within the guide. Nineteen eighty-three, thoughts you, had the best charge of unemployment on report within the final 70 years. It was the devastating impact of Reaganomics, neoliberalism and globalization on Black city industrial employees. What’s attention-grabbing is how a disaster that affected Black ladies simply as a lot as Black males obtained recast by Black male leaders (on this case Ebony’s [executive] editor … Lerone Bennett) as a gendered disaster affecting solely Black males. In his letter from the editor, he harped on the difficulty you carry up—that Black male “disaster” may very well be measured in faculty enrollments. School enrollments for all African Individuals have been up from the earlier decade, nevertheless. What the “disaster” was for Bennett (who [was] a Morehouse alumnus) was that Black males have been outnumbered by Black ladies on faculty campuses for the primary time.  So, that is one thing to bear in mind about what insights Respectable presents about how this rhetoric about “disaster” will get articulated and propagandized by gender. Black male faculty enrollments—like all faculty enrollments—are nonetheless up in comparison with earlier generations however did take a 14.3 percent drop in spring 2021 in comparison with spring 2020, however Black enrollment over all declined a whopping 8 percent throughout the pandemic, notably at neighborhood schools, the place Black enrollments declined 13 percent. However how are we speaking about this subject that affects Black males and ladies on faculty campuses? It’s not being articulated because the disaster of Black neighborhood faculty college students—it’s articulated because the disaster of Black males. Authorized scholar Paul Butler coined a time period for this, known as “Black male exceptionalism,” i.e., when points affecting the race writ massive are articulated as disproportionately or solely affecting Black males. There are points that disproportionately have an effect on Black males, comparable to mass incarceration (males over all make up most incarcerated individuals, whereas Black incarceration rates have fallen 34 percent since 2006) however Black male exceptionalism offers a approach of singling out Black males whereas obscuring how these points penalize different teams disproportionately as properly. We’ve no purpose to imagine Black faculty ladies’s enrollments are holding regular within the pandemic, however you’ll be hard-pressed to even discover the stats on Black ladies’s pandemic enrollment numbers, as a result of there isn’t a political exigency to trace points that have an effect on Black ladies. Low-income and first-generation Black college students have traditionally accessed neighborhood schools greater than different African Individuals, so why isn’t this 13 p.c drop seen as an pressing matter of entry inequality for probably the most underprivileged Black college students? So, sure, Black enrollment declines within the pandemic are of nice concern, particularly on the two-year faculty degree, however we miss the image once we misleadingly articulate these points as Black male points, as if different demographics of Black individuals aren’t harmed as properly. That’s an enormous a part of what my guide tackles—how the rhetoric of Black male disaster misses the scope of those points, and, thus, methods to redress them, if we don’t seize how race, class and gender work in conjunction.

So, that is one thing to bear in mind about what insights Respectable presents about how this rhetoric about “disaster” will get articulated and propagandized by gender. Black male faculty enrollments—like all faculty enrollments—are nonetheless up in comparison with earlier generations however did take a 14.3 percent drop in spring 2021 in comparison with spring 2020, however Black enrollment over all declined a whopping 8 percent throughout the pandemic, notably at neighborhood schools, the place Black enrollments declined 13 percent. However how are we speaking about this subject that affects Black males and ladies on faculty campuses? It’s not being articulated because the disaster of Black neighborhood faculty college students—it’s articulated because the disaster of Black males. Authorized scholar Paul Butler coined a time period for this, known as “Black male exceptionalism,” i.e., when points affecting the race writ massive are articulated as disproportionately or solely affecting Black males. There are points that disproportionately have an effect on Black males, comparable to mass incarceration (males over all make up most incarcerated individuals, whereas Black incarceration rates have fallen 34 percent since 2006) however Black male exceptionalism offers a approach of singling out Black males whereas obscuring how these points penalize different teams disproportionately as properly. We’ve no purpose to imagine Black faculty ladies’s enrollments are holding regular within the pandemic, however you’ll be hard-pressed to even discover the stats on Black ladies’s pandemic enrollment numbers, as a result of there isn’t a political exigency to trace points that have an effect on Black ladies. Low-income and first-generation Black college students have traditionally accessed neighborhood schools greater than different African Individuals, so why isn’t this 13 p.c drop seen as an pressing matter of entry inequality for probably the most underprivileged Black college students? So, sure, Black enrollment declines within the pandemic are of nice concern, particularly on the two-year faculty degree, however we miss the image once we misleadingly articulate these points as Black male points, as if different demographics of Black individuals aren’t harmed as properly. That’s an enormous a part of what my guide tackles—how the rhetoric of Black male disaster misses the scope of those points, and, thus, methods to redress them, if we don’t seize how race, class and gender work in conjunction.

Q: You write that being a graduate of Spelman School makes you each an insider and an outsider to the Morehouse alumni neighborhood. What was it like so that you can write this guide from that perspective?

A: It’s like respecting the troopers and critiquing the army. That’s the way it feels as a Spelman girl to have so many shut bonds with Morehouse graduates. The core of my grownup life when it comes to how I’m plugged into Black America from coast to coast is de facto based mostly in my “SpelHouse” household. My faculty expertise was the primary time I spotted how America should really feel for white individuals. I used to be in a spot that was all about younger individuals like me, the place the curriculum mirrored me, the place I by no means fearful about being second-guessed and the place, for the primary time in my life, I might discover all of the complexities of myself with out the white gaze collapsing all of me right into a single lens of Black inferiority. So to say I cherished my faculty expertise is an understatement. I felt free there. What bothered me a lot was realizing there have been different Black individuals who have been queer or gender-nonconforming or low revenue, and many others., who couldn’t be happy there. It doesn’t sit properly with me that Black schools aren’t havens for marginalized Black individuals, who catch hell inside the race.

I say within the guide that “the most effective males I do know went to Morehouse and the worst males I do know went to Morehouse,” and that continues to be true for me. As a result of I’ve such an insider perspective on this establishment, I’m very cautious to not piece aside the lads from the institutionalization course of. These males had various ranges of objection to those institutional processes themselves, so my job as an ethnographer is to place their tales into a bigger context that possibly they don’t even have—possibly they thought they have been the one ones pondering this and possibly they’ve by no means thought of how these points match into an extended arc of over a century of Black gender politics. That’s my outsider, proper? The socio-historical lens I utilized to this examine as a researcher. However I at all times crafted that lens with the duty and love of an insider. Due to misogyny inside Black areas, there are various who would solid any critique Black feminists have of Black males and masculinity as man-hating and even betraying the race by “airing our soiled laundry.” However certainly one of my Morehouse classmates stated it finest. He stated, “Saida loves Morehouse as a result of she is aware of we will do higher.” There are those that would wrongly decide this guide prima facie as some disdain I’ve for Morehouse. To that I say what James Baldwin stated about America: that he cherished his nation and subsequently reserved the best to be fiercely crucial of it. I really like the components of Morehouse that Morehouse usually doesn’t love—the queer, working-class, trans and gender-nonconforming Morehouse. These are Black individuals who without end solid outdoors of Morehouse whilst they’re college students inside it. In the event that they have been cherished and affirmed like they belonged inside this establishment, then I wouldn’t have a guide to jot down.